Retrieval-augmented generation for docs, part 1

Retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) is a technique that enables large language models (LLMs) to retrieve and incorporate new information from external data sources. This information supplements the LLM’s pre-existing training data.

When we talk about RAG in the context of documentation search, we mean that a large language model retrieves and incorporates documentation content, then uses this content to generate a response to a query.

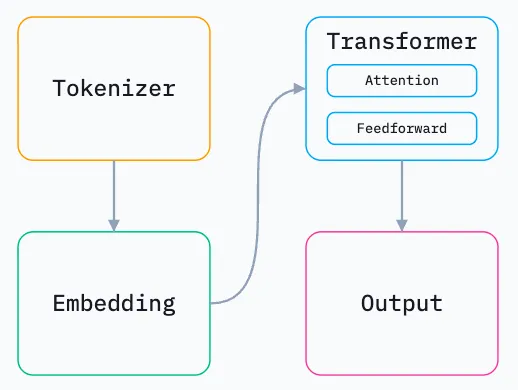

Before we go further, we need to understand the basics of how LLMs work, courtesy of Sam Rose at ngrok.

An overview of LLM architecture

When discussing token caching, Sam Rose of ngrok has this to say about LLMs:1

At their core, LLMs are giant mathematical functions. They take a sequence of numbers as input, and produce a number as output. Inside the LLM there is an enormous graph of billions of carefully arranged operations that transform the input numbers into an output number.

This enormous graph of operations can be roughly split into 4 parts.

I mainly want to go over the first two stages.

Tokenizer

The tokenizer takes your prompt, chops it up into small chunks, and assigns each unique chunk an integer ID called a “token.” Tokens are the fundamental unit of input and output for LLMs, and each integer ID represents a particular chunk.

Each LLM tokenizes in its own way.

Embedding

Tokens are fed to the embedding stage.

When the LLM was trained, the training process mapped all possible tokens to positions in n-dimensional space. The embedding stage takes the token IDs, and converts them to the token’s position in n-dimensional space2. Each token becomes an array of length n, so we gain an array of arrays — a matrix.

The embedding stage also adds each token’s position within the prompt. This is required for the LLM to know the order of tokens in the prompt.

You may also come across the word “vector.” The numbers in an embedding array constitute a vector, in a mathematical sense. Embeddings are the name we give to vectors that capture the semantic meaning of words, sentences or even entire documents.

If you’re not sure whether to use “vector” or “embedding,” here’s how I think about the choice:

- Vectors are numbers in an array. If we’re just talking about the math, we can call the array a vector.

- Embeddings are about meaning. A vector is called an “embedding” because we are figuring out where information is embedded in

n-dimensional space.

The other stages

The other stages involve a lot of math, particularly matrix multiplication, to figure out the relationship between all the tokens and move them around n-dimensional space.

To understand what I’m doing for RAG, however, we don’t need to understand the transformer and output stages.

RAG and documentation

Back to retrieval-augmented generation (RAG).

As retrieval-augmented generation is an LLM-based text generation technique, our documentation has to go through a journey to get to your answer. Here is an overview of how data could go from start to answer:

- Loading: Retrieve the data that needs to be indexed and searched later.

- Indexing: Convert loaded documents into vector embeddings. The embeddings help the LLMs find relevant information even if queries use different words.

- Storing: Save your embeddings and metadata.

- Querying: A user asks a question in your search interface. The search application transforms the query into an embedding and searches the indexed data for the most relevant text chunks. It can also apply other search strategies to improve results.

- Generation: The retrieved context and user query go to an LLM, which crafts a human-like answer from specific data.

This is the core of any RAG application: index your content semantically, then search your content by meaning.

Loading is a matter of “have the data,” so we’ll go straight to…

Indexing (vectorizing)

The indexing stage is all about creating a vectorized index of your data.

In the RAG/search context, vectorizing means converting pieces of content into numerical representations (vectors) such that semantic similarity becomes geometric proximity. We don’t index documents or pages; we try to index meaningful units of knowledge. Vector search systems are structure-agnostic unless we explicitly provide structure as metadata.

Vectorization is not:

- Full-text indexing (like Lunr or Elasticsearch keyword search).

- Page-level indexing only.

- Storing HTML or Markdown as-is.

- Automatically “understanding” documentation structure unless you encode it.

- A goal. Vectorization is a part of a strategy to support specific user questions more effectively than keyword search.

Vectorizing is a critical part of the RAG pipeline; I’ll spend more time explaining it.

What gets vectorized?

In the context of documentation, a documentation site is already a structured knowledge system. Vectorization involves deciding which parts of that structure become semantic units.

In practice, you vectorize chunks, not whole pages. Typical chunk boundaries for documentation might be:

- Section or subsection (most common)

- A heading plus its following paragraphs

- A fixed token/character window with overlap

For documentation sites created by static site generators, natural chunk boundaries already exist:

| Element | Vectorization relevance |

|---|---|

| Page (text file with markup) | Too coarse on its own |

| Header-tagged sections | Ideal chunk boundaries |

| Paragraph blocks | Often too small alone |

| Admonitions | Usually included, sometimes tagged |

| Lists | Included as text |

| Tables | Included, but flattened |

| Code blocks | Special handling |

From my research, a good rule of thumb is that one chunk is roughly equivalent to one idea someone might search for.

What text is actually embedded?

From each chunk, you typically embed the human-readable instructional content in plain text form. Concretely, this usually includes:

- Headings (very important for context)

- Paragraph text

- List items

- Admonition content (notes, warnings, tips)

This content usually excludes or down-weights:

- Navigation chrome

- Sidebars

- Repeated boilerplate

- Copyright footers

Dealing with code blocks

How you handle code blocks is a design decision, not an automatic win. A few options exist, according to my own queries to an LLM:

- Embed code as text (works surprisingly well for API-style queries.

- Exclude code from embeddings, but keep it retrievable via metadata.

- Embed code separately, as its own chunk type.

For RAG on technical docs, option 1 or 3 are usually superior (supposedly)

Metadata: the hidden half of vectorization

Embeddings alone are not enough to be successful. If you really want to make RAG work, every embedded chunk should carry metadata. For a documentation site, metadata may include:

- Page title

- URL / slug

- Section heading path (Page > Section > Subsection)

- Product / version

- Doc category (tutorial, reference, concept)

- Language

- Source file path

This metadata is usually not embedded as part of the vector. It can be used for filtering, ranking, and attribution. If you want a usable RAG answer, good metadata is critical; a vector without metadata is a point in space with little to no meaning attached.

Content other than the main docs

Beyond general docs pages, one may want to vectorize the following content:

- Versioned documentation, with either separate vector indexes or metadata filters

- Blog posts

- API documentation, with different chunking rules and metadata

How to vectorize

There’s a critical part of vectorization I didn’t touch on: how you actually do it.

In practice, this is done by large language models as well. You have to find an LLM specifically designed to create embeddings, and feed it all your content chunks. The embedding LLM does all the math for you.

You need a computer program or script that does this part. You also need to choose the embedding model. Different models yield different results, which must be discovered by testing or by reading benchmarks. Or both.

Storing

Compared to what we needed to understand up to this point, I find the storing part of the pipeline straightforward: you have to save your embeddings index somewhere, and make it accessible to a query system. That’s it, with a catch: remember to store the actual content chunks as well! The search system needs to know about them later.

How you store your index is mainly a technical decision:

- If you’re testing RAG on a local machine, then you might be storing the index as a local file.

- If you’re building a RAG application for the internet to use, you could store your index online.

- Cloud service providers have databases that are designed to store vectors efficiently.

In the end, we’re storing text and numbers. Maybe a lot of text and numbers, but still text and numbers.

Querying

By the time you reach the querying stage, your documentation has been vectorized into documentation embeddings; embeddings are enriched by metadata; the embeddings index and content have been stored somewhere. Now what?

At query time, a search application performs these tasks:

- The search application receives the user query.

- It vectorizes the user query, turning the query into an embedding of its own.

- It compares the query vector against the vectors in the stored embeddings index.

- Based on which embeddings were considered the closest, the application retrieves

xcontent chunks it considers to be the most relevant to the query (wherexis configured in the application) - It injects the retrieved chunks into an LLM prompt that also contains the user query.

- The LLM gives an answer based on the content it was fed.

The quality of the answer is dominated by:

- Chunk quality

- Chunk boundaries

- Metadata quality

- Exclusion of noise

- Choice of large language model

If everything went right, you now have a working answer, and successfully reached the end of your RAG pipeline.

Summary

Retrieval-augmented changes how documentation can be searched and consumed. Instead of relying on keywords or page boundaries, ideas are embedded as vectors, retrieved by meaning, and combined with an LLM to generate context-aware answers.

Making this work well requires you to think about knowledge chunks, deciding what to embed, and including metadata that preserves structure, provenance, and intent. And even then, there are catches along the way.

In another post, I’ll attempt to implement a RAG system for documentation.

Footnotes

-

What number does

ncorrespond to? In short, whatever, the LLM designer wanted it to. Adding dimensions increases the model accuracy, but makes it more computationally intensive. ↩